For Australians in France 11 November is a sombre day. I am not alone in having a great grandfather who survived Gallipoli only to be gravely wounded in France. The vast majority of Australia’s dead in the First World War fell defending France. Australian losses pale in comparison to 1.6 million French who lost their lives.

For Australians in France 11 November is a sombre day. I am not alone in having a great grandfather who survived Gallipoli only to be gravely wounded in France. The vast majority of Australia’s dead in the First World War fell defending France. Australian losses pale in comparison to 1.6 million French who lost their lives.

In the face of such a catastrophe, it is often said that we should never again fight wars. Australia and France, who have fought together most recently in Syria, know that this is not possible. Rather we need to know whether, as democracies, our countries can make sound decisions about war and peace.

There are two widely held beliefs about how a democracy takes such decisions. The first opinion holds that democracy is simply bad at waging wars. It assumes that the fear that democratic politicians have of voters prevents them from introducing the tough policies that security requires. This opinion also holds that democratic freedoms undermine military discipline.

This belief continues to have a big impact in contemporary politics. Democratic politicians sometimes use it to justify their suppression of public debate or even democratic freedoms. The result can be a disaster such as the Iraq War of 2003.

The second belief is one that we have cherished since the Second World War. It assumes that democracies are peace-seeking. Their voters, according to this opinion, do not like violence in international relations and so prefer to resolve conflicts peacefully. They believe that democracies are reluctant to wage war and never fight each other.

This second belief has had no less of an impact on the contemporary world. President Bush used this belief to justify his invasion of Iraq in 2003. By making Iraq democratic, he argued, the United States would be bring peace to the Middle East.

This opinion often can also make us underestimate what peace requires. We think that our democratic institutions alone reduce the likelihood of war. As democrats, we believe that we are simply pacifists by definition.

Both of these beliefs continue to influence contemporary politics for good or ill. Consequently it is necessary to ask ourselves whether they are correct. A possible way to answer this question is to study past democracies. Such democratic histories can show us whether these beliefs are true or false, with classical Athens being one such historical example.

Some might think that there is nothing to learn from the ancient Greeks. But this was not what our great grandfathers thought. Australia and France fought together for the first time against the Turks at Gallipoli. There the Australians were greatly impressed by the Greek artefacts that they found in their trenches.

At Cape Helles French did one better. In June 1915 General H. Gourand gave the order to begin excavations under artillery fire. For Gourand it was a question of national honour: these excavations would demonstrate to the world the strength of France’s cultural values even in the midst of terrible suffering. While thousand died all around them, French archaeologists discovered a large part of the lost Greek city of Elaious. Today their important discoveries are displayed in the Louvre.

At Cape Helles French did one better. In June 1915 General H. Gourand gave the order to begin excavations under artillery fire. For Gourand it was a question of national honour: these excavations would demonstrate to the world the strength of France’s cultural values even in the midst of terrible suffering. While thousand died all around them, French archaeologists discovered a large part of the lost Greek city of Elaious. Today their important discoveries are displayed in the Louvre.

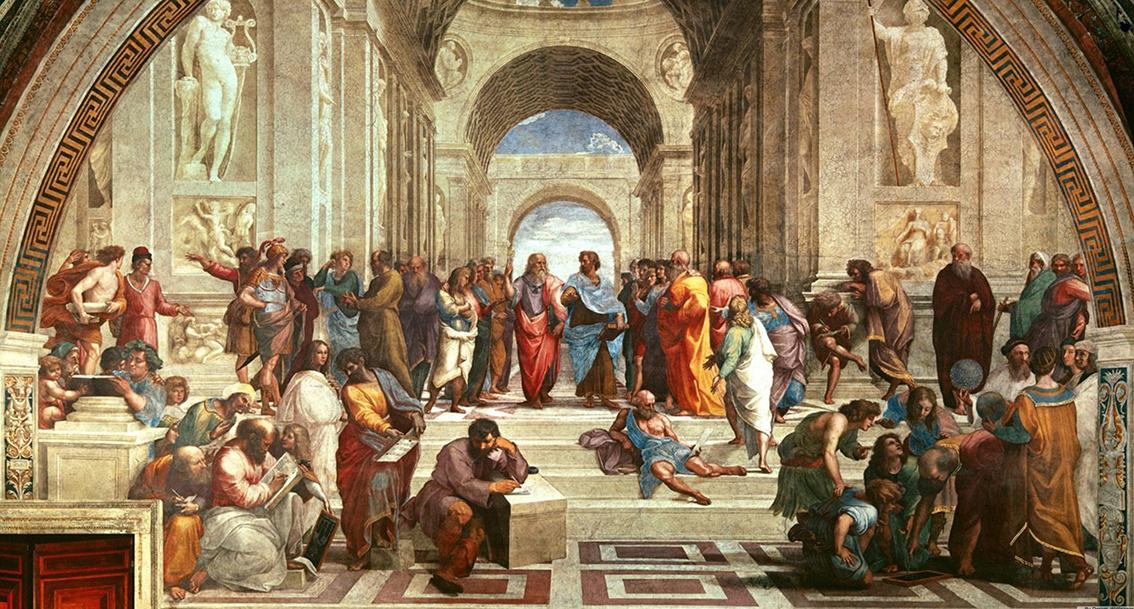

When we think about classical Athens, the two things that come immediately to mind are democracy and culture. This is not so surprising. In this city poor citizens in their thousands decided directly what their state would do. The Athenians developed democracy to a higher level than all other states before modern times. Their democracy was also without a doubt the cultural innovator of its age. We still admire the Parthenon and continue to stage Athenian plays.

When we think of this city, however, what does not often come to mind is war. Yet, war was the flipside of these political and cultural successes. The Athenians transformed the art of war and created the best armed forces of ancient Greece. Their democracy quickly became a superpower and hence could impose democracy on others by force. Perhaps what is the most surprising is that democracy itself was the main reason for this military success.

The military impact of democratic politics in Athens was twofold. The staging of plays as well as political debates in front of working-class citizens created a pro-war culture. This militarism encouraged increasing numbers of poor Athenians to join the armed forces and to vote more often in favour of wars.

All this was counterbalanced by the debates about war that Athenian democracy supported. These debates reduced the risk of this cultural militarism because they forced citizens to assess thoroughly all proposals for wars and the running of military campaigns. They also facilitated the introduction of military reforms. Democratic debate taught Athenian combatants as well to take initiative during military campaigns.

This unexpected record of democratic military success refutes the belief that democracies are bad at wars. In fact, what made Athens a superpower were its democratic institutions. There seems no reason to doubt then that democracies can be good at waging wars. Public debate and democratic freedoms play the crucial roles in this military success. By supressing them we simply reduce drastically the advantage that democracy gives us in international relations.

Classical Athens, however, also calls into question the belief that democracy leads to peace. The Athenians were better democrats than we are. At the same time the democracy that they had perfected did not stop them from creating a veritable killing machine. They waged war nonstop for two centuries. In doing so, they unleashed unprecedented destruction on ancient Greece and killed civilians by their thousands.

For us classical Athens must therefore serve as a warning. Democratic institutions do not automatically make us pacifists. When we search for peace, other things must come to mind: peaceful values, shared identities and conciliatory public discourses. If we truly want peace, these are the things that we need to foster at home and abroad.

David M. Pritchard is a research fellow at the Institute of Advanced Studies of the University of Lyon where he is also an associate member of HiSoMA. He is Associate Professor of Greek History at the University of Queensland and the author of Athenian Democracy at War (Cambridge University Press 2019).

Le Figaro published this piece in French on 11 November 2019. You can find a copy of this French version here.